Computers have become an integral part of diving as they make the sport safer, allowing us to monitor data about the dive in real-time. As we will cover later on in this article, computers have allowed divers to safely follow a multi-level plan (meaning staying at increasingly shallower depths during the same dive) instead of single-depth dives. Let's have a look at what dive computers are, which types exist, and how to use them, while also looking into some key features of dive computers. At the end of this article, there will be a buyer's guide about purchasing your dive computer.

If you're interested in learning more about the equipment scuba divers use, check out this article, which talks about all the equipment pieces.

What is a Dive Computer

Dive computers (or diving computers) are to divers what a speedometer is to a car: they are a piece of equipment that is part of what we call the information system. The computer displays information about the dive in real-time, allowing the divers to monitor their dive and adjust their plan accordingly (follow a certain depth, not exceeding a no-decompression limit, etc...). Dive computers have a dive-logging system, allowing divers to view certain informations about their past dives (such as date, time, max depth, temperature, etc...).

As we will see in this article, dive computers are very easy and straightforward to use for monitoring basic information such as depth and dive time, but have additional modes and can be used very intricately for purposes such as technical diving.

Using a Dive computer

Dive computers are not part of the main scuba unit and, although extremely useful for helping keep the diver within safe limits, they are not a mandatory piece of equipment in many dive centers. Therefore, dive computers are used as a complementary part of the equipment, assisting divers.

Modes

Let's have a look at the different modes that exist on dive computers.

Diving mode:

The "diving mode" activates when the computer is immersed (dive computers usually have an activation threshold such as 0.5m or 1m, which depends on the model of the computer). This mode displays all the information the diver needs while submerged, such as: current depth, max depth, dive time, no-decompression limit, etc...

Some more advanced dive computers have more detailed information, such as the average depth of the ongoing dive, the nitrogen loading level for each tissue in the body, a display of the dive profile, etc... Using the buttons on those dive computers allows you to cycle between the displayed information.

When ending the dive and surfacing, the computer usually has a countdown of a few minutes before exiting the dive mode and logging the dive.

Air or EANx mode: During the dive, the computer tracks the on/off-gassing of nitrogen in our tissues and imposes a no-decompression limit (or mandatory decompression stops if the limit is exceeded). The air or nitrox mode allows the dive computer to adapt the nitrogen saturation speed in our tissues depending on the mix the diver is using. Using an EAN (Enriched Air Nitrox) blend and setting the computer on nitrox mode with the correct mix (you will need to set the exact oxygen percentage -from 21% to 100%- that is in your mix) will allow the diver to extend their bottom time. The dive computer will also automatically calculate the MOD (Maximum Operating Depth) of each mix and warn the diver with an alarm if that depth is exceeded.

For shallow dives (if the MOD of the mix is respected), it is entirely possible to breathe a nitrox mix while leaving the computer in air mode, however, you should never breathe air while leaving the computer on nitrox mode, as you will encur a risk of on-gasing more nitrogen then the computer takes into account and getting DCS-related complications.

Freediving or Gauge mode: for freedivers, the computer has a mode (usually called freediving, gauge, ot bottom timer mode), allowing the user to monitor their depth during a freedive descent without tracking the on/off-gassing of nitrogen. As its name entails, in this mode, the computer will act as a gauge. When scuba-diving, the diver must ensure the computer is NOT in gauge mode as they need to constantly monitor their nitrogen level and perform any potential stops (either safety stop or decompression stop) that the computer wouldn't give while it is in gauge mode.

Multigas mode: the multigas mode allows the diver to add one or more extra gas mix as a preset. During the dive, the diver can then switch from one mix to another. This is especially used for technical dives, during accelerated decompression, when the diver switches from a low-oxygen mix to a high-oxygen mix. Most basic computers allow one extra mix (usually limited to nitrox), while more advanced computers allow for more than two mixes (with trimix and helium mix usually supported).

Changing the gas mix on the computer is usually the last step of a full gas switch procedure.

Surface mode: While the user isn't diving, the surface mode allows them to access their logged dives, change dive settings, adjust the gas mix for future dives, and more. Some modern dive computers can also be used as a lifestyle/fitness watch while in surface mode.

Features

Modern dive computers have many features, giving the diver more control over their dive. Let's have a look at all the features available in modern dive computers!

Monitoring dive information: although this is the most basic feature, a dive computer wouldn't be a dive computer without it! Basic information includes current depth, max depth, and dive time. We recommend divers to wear their computer on their right arm, to enable them to monitor their depth on one hand, while holding the inflator hose in the other.

Tracking your NDL: A big advantage of dive computers, compared to the old dive tables, is that there is a real-time tracking of the nitrogen on-gassing, allowing it to calculate a so-called NDL (Standing for No-Decompression Limit). The No-Decompression limit is a number, in minutes, telling the diver how long they can stay at a specific depth without having a required decompression stop (or multiple decompression stops) to perform. The NDL is dynamic, meaning it is constantly recalculated by the dive computer: this is very useful in recreational deep dives, as it allows the diver to go to their target depth, approach their NDL, and slowly ascend to re-increase the NDL (this allows the diver to follow what we call a multi-level dive, instead of the single-level dives described in the old dive tables).

Conservatism: Conservatism is a setting allowing the diver to be more tolerant (less conservative) or less tolerant (more conservative) of the nitrogen saturation in the body. A more conservative setting will make the computer shorten the NDL and make it arrive in deco faster; it will also ensure the diver exits the water with less nitrogen (conversely, a less conservative setting will extend the bottom time and allow the diver to exit the water with more nitrogen in their body).

More advanced dive computers will allow the user to change their high and low gradient factors (see gradient factors) to allow them to have more control over their decompression plan.

Decompression plan: when the no-decompression limit is exceeded, the dive computer will provide the diver with a decompression plan to follow, giving specific depth(s) for the diver to stay at for a specific time before ascending, allowing the nitrogen to leave the body before surfacing.

Dive computers that are specifically made for technical and decompression dives have more adjustable parameters, giving the diver more control over their decompression plan (some examples of those parameters are high/low gradient factors, depth of last stop, step between each decompression stop, etc...). To plan a decompression dive, technical divers will use a combination of pre-dive planning software (such as Multideco) to ensure they are within their limits (maximum allowed decompression time, enough gas to complete the dive while respecting the rule of thirds, etc...), and then respecting the decompression plan given by their computer while on the dive (not all technical dives are necessarily planned this way, this is just one of many ways).

The safety stop given by a dive computer is not a decompression stop. A typical safety stop (5m for 3 minutes at the end of a dive) is an additional safety precaution taken by divers, while a decompression stop is a mandatory stop, where the diver needs to bring down their tissue nitrogen saturation to a safe level before surfacing.

Monitoring Nitrogen level: In modern dive computers, the nitrogen saturation level of the tissues in the body can be tracked and/or visualized, giving an idea to the diver just how much nitrogen is in their body. For instance, the surface gradient (or gradient at the surface) lets the diver know just how saturated their most saturated tissue is (as a percentage of the maximum tolerated value at the surface, also called M-value). For example, a diver with a surface gradient of 70% knows that their most saturated tissue is at 70% of its M-value at the surface.

A popular decompression model used by many dive computers is the Bühlmann ZHL-16, which tracks the nitrogen saturation of 16 distinct compartments (with each tissue on/off-gassing at a different speed). Some dive computers show a graph of each compartment with its nitrogen saturation level. This is very interesting information for divers (both from a technical and an educational standpoint).

Monitoring Ascent Rate: The ascent rate is simply the speed at which the diver goes up (expressed in meters/minute or feet/minute). To avoid any overexpansion injuries and/or DCS-related complications, each diving agency gives a safe limit for the ascent rate to respect: For example, SSI sets the safe limit for the ascent rate at 9 meters/minute (or 30 feet/minute), while PADI sets the safe limit at 18 meters/minute (or 60 feet/minute).

The computer measures the depth at two different points in time and uses the difference in depth to calculate the average speed of ascent. If the ascent speed is faster than the safe limit, the computer's alarm will ring, alerting the diver to slow down.

Logbook: When the dive is over, it is saved in the internal memory of the dive computer and can be reviewed at a later point in time. The logbook usually holds the most important informations about the dive, such as:

- Dive time

- Date and time of entry

- Maximum depth

- Average depth

- Minimum/maximum temperature

- Dive profile

In some dive computers, you can also review general information about all the dives, such as the total number of dives, or even information about the deepest or longest dive. Modern computers very often have an "automatic upload" functionality, allowing them to upload the new dives to a mobile application, logging them on the phone (Shearwater and Garmin are examples of dive computers that allow the user to do that).

Backlight: The backlight is a feature that allows a dive computer to light up its screen and be readable in a dark environment. Some more advanced dive computers have naturally bright screens, not requiring any backlighting. To activate the backlight during a dive, there is either a dedicated button (labeled "light") or the user may have to long-press another button. In the dive settings, you can set the duration of the backlight (meaning, how long the dive computer stays lit up).

Air integration: The air integration is a feature in dive computers that allows the diver to attach a specific transmitter (usually sold separately) to a high-pressure port on their first stage, which transmits the pressure it reads to the dive computer. As such, the diver can monitor their tank pressure directly from their dive computer.

Computers with air integration generally calculate the SAC (surface air consumption) rate for the diver, giving additional information, such as time to reserve, which estimates how much time remains for the diver until they reach their reserve pressure.

Compass: Only found in advanced dive computers, a magnetic sensor/compass module allows the diver to use their computer as a compass. Before using the compass, the user must ensure that the compass is calibrated and/or the magnetic declination is correctly set. For dives requiring heavy navigation, we recommend also carrying a regular diving compass.

Safety Stop: As mentioned before, a safety stop is a stop generated at the end of a dive (usually at 5 meters for 3 minutes), giving a bit more time for the nitrogen in our body to exit before surfacing. In some computer models, a safety stop is generated only a certain minimum depth is exceeded: for example, a Mares Puck Pro will not generate a safety stop if the diver does not go below 10 meters (33 feet). The safety stop timer starts automatically once the diver reaches a certain depth (usually 6 or 5 meters). If the diver accidentally goes below that depth, the safety stop pauses, only resuming once the diver reascends.

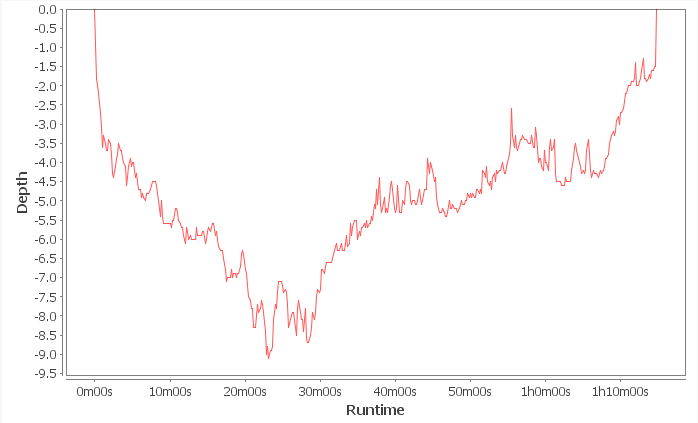

Dive profile: The dive profile is a graph representing the depth of the diver as a function of time. It shows the path the diver took (only depth-wise) during the dive. The dive profile can either be reviewed from the logbook menu, or in some cases, a dive profile may be generated in real time during the dive.

An ideal dive profile is steady, where the diver avoids going up and down (the profile shown above doesn't look steady at first, but the "spikes" are actually only about 1m of depth difference). Divers should also avoid reverse dive profiles, where they go to a certain depth, then shallow up, before going back down to a deeper depth.

To learn more about dive profiles, read this article.

Temperature: Monitoring temperature is an important task as it give information to the diver as to what suit thickness will be more appropriate to wear, how temperature changes with depth, amongst other things.

During a dive, the temperature will be shown in real-time, and after the dive, the computer usually gives the minimum and maximum temperatures of each logged dive. Knowing the water temperature can help the diver prepare appropriately and stay comfortable during the dive.

Gradient Factors: Gradient factors are too vast a topic to cover in a small paragraph and not have their own article (and therefore, here is the full article about gradient factors), but here is the gist of gradient factors:

Gradient factors consist of two separate percentages, GF high and GF low. "GF high" represents the maximum allowed tissue nitrogen saturation in the most saturated tissue (expressed as a percentage of its M-Value), while "GF low" is the value that will generate the depth of the first stop (also expressed as a percentage of the M-value of the respective tissue). Dive computers geared towards decompression dives allow the divers to set their own gradient factors (either with presets or by manually setting them), allowing a more in-depth personalization of the decompression plan.

Oxygen clock: Oxygen, at higher partial pressure, can be toxic to the body (read more about oxygen toxicity here), especially for prolonged durations. One way our dive computers help us in keeping track of the exposure to oxygen is with the CNS value.

The CNS value (which is expressed as a percentage) represents how close the body is to the safe limit of the safe limit for oxygen. By knowing which gas mix the diver is breathing, the dive computer can calculate the CNS value in real time: The CNS value increases the more the diver is exposed to high (> 0.6 atm) ppO2 (of course, the higher the ppO2 is, the faster the CNS value increases). This is especially important information to know for decompression dives, where the diver is exposed to very high partial pressures of oxygen during decompression stops.

Planning your dive

Dive computers have revolutionized the way divers plan their dives, making it easier and safer to plan a dive than with dive tables. Let's have a look at how a diver can use a dive computer to plan their dive:

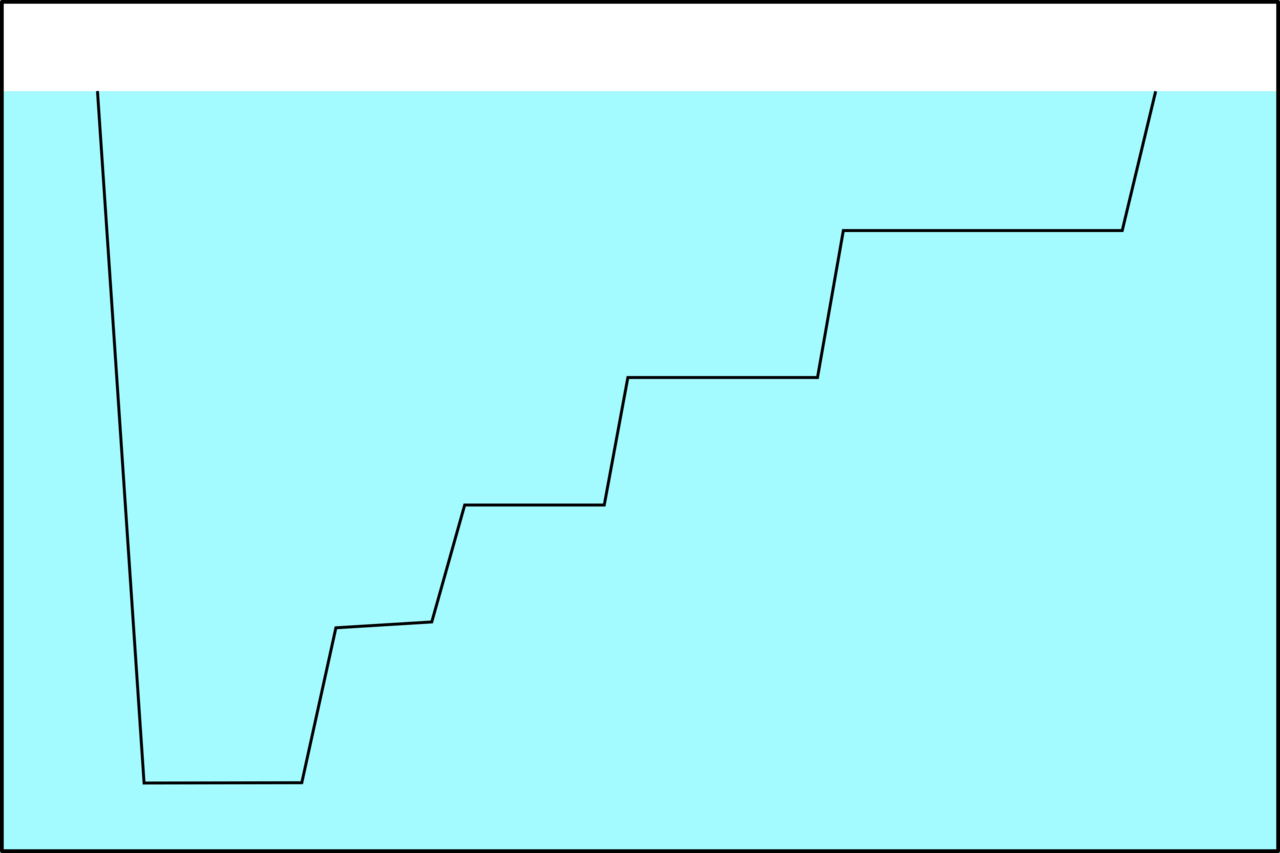

Multi-level dives: Multi-level dives are dives where the diver is able to stay at multiple (increasingly shallower) depths for different amounts of time. A single-level dive, by contrast, is a dive where the diver goes to a certain depth before re-ascending to the surface (such dives can be planned using dive tables).

Computers, thanks to being able to calculate the No-Decompression limit in real-time, enable the diver to manage it by continuously reducing their depth, ensuring the NDL always stays above zero.

To give an example of a multi-level dive, imagine you are exploring a wreck that lies at a depth of 35m. You would start the dive by going to the deepest planned depth (35m). With your group, you agree on a minimum NDL to respect (for example, you could agree to not go under an NDL of 5 minutes): once that NDL is reached, you are going to start to ascend; this doesn't mean you are going straight back to the surface, but you're going to shallow up (perhaps the wrecks has an upper deck, a captain's cabin that is shallower, or even a mast) gradually, until the NDL increases to a safe level. You could, for example, want to swim above the wreck at a depth of 28m. As you shallow up, the NDL is going to increase, giving you additional time at increasingly shallower depths.

Multi-level dive profiles are great for extending the dive time, and are the norm for most modern dive plans. Below is a graph showing an example of a multi-level dive profile:

Pre-planning your dive: Dive computers can let the user pre-plan a dive. This can be done in a variety of ways: for instance, they can choose a planned depth, where the computer will ring its alarm when the depth is reached/when it is exceeded. By using that feature, the computer (knowing which gas mix the diver will use) will calculate the no-decompression limit at that depth and give the result before even entering the water.

Decompression using a dive computer: When doing decompression dives, a dive computer is essential. On top of planning the decompression plan before the dive using a decompression-planning software (such as multi-deco or V-planner), a computer is necessary to monitor the maximum depth, the total deco time, the time-to-surface, the runtime, and more.

When the diver starts ascending and completing his decompression obligations, it will give the required depths the diver must stop at and the duration (for each separate depth). As technical dives should be prepared and completed thoroughly, the diver shouldn't rely just on a single computer. It is standard practice for technical divers to have a backup computer alongside their main computer.

Dive computer mistakes

Exceeding NDL: When diving recreationally, one of the rules that is needs to be followed is to stay "within recreational limits", which means that the No-Decompression limit shouldn't be exceeded: this means that at any time during the dive, the diver can ascend to the surface without necessary decompression stops.

If this rule isn't followed, it can lead to some issues: firstly, if the diver exceeds the no-decompression limit, it means he/she has too much nitrogen in their body to ascend directly to the surface, and must perform mandatory decompression stops before ascending. If the diver isn't trained to perform decompression stops properly and/or doesn't master their buoyancy, it can put them at risk. Secondly, some recreational-only dive insurance might not cover any dive-related injury/issue if the NDL is exceeded.

Divers should only enter decompression if they are trained for it, if it is planned, and if they have the appropriate equipment.

Using Wrong Gases: Using the wrong gas on the dive computer is usually more of an inattention error rather than a mistake. Having the incorrect gas set on the dive computer can lead to dangerous situations for the diver: if the dive computer is accidentally set on Nitrox mode while the diver is breathing air, the nitrogen intake in the blood and tissues won't be correctly monitored, which can falsely extend the no-decompression limit. This is especially problematic on deeper dives, where the tissues of the diver saturate with nitrogen faster.

For technical dives, this is equally (if not more) important, as it is crucial for the diver to know how much decompression they require, what depth they can change their mix at, etc...

Not checking the battery: Dive computers are electronics and therefore require a battery to operate. If the battery is empty or defective, the dive computer will simply not turn on! Some dive computers let the user know exactly how full the battery is, while others only give an alert when the battery is almost empty. In any case, we recommend turning the computer on before any dives and looking at the battery level. If the battery level is insufficient for the dive (or if the computer doesn't even turn on!), abort the dive.

If you are planning a diving vacation, charge your computer fully or change the battery for a new one. Some dive computers require a certified technician to change the battery. For more information, check your computer's user manual.

Care and Maintenance Tips

Computers are important (and possibly expensive) components of your equipment, and as such, they should be taken care of, regularly maintained, and serviced.

Before and after a dive, avoid leaving your computer on the floor, as it risks getting stolen or accidentally stepped on: either keep it on your wrist or leave it clipped onto your assembled kit. Ensure the screen of the computer isn't facing down, as you risk scratching it.

During the dive, don't exceed the maximum tolerated depth of your dive computer. This usually isn't an issue for recreational divers, as most dive computers are rated to a depth greater than 40m (131 feet), which is the recreational limit; However, for technical divers, who may venture deeper, this depth rating is something that needs to be taken into account.

After the dive is finished, clean the computer with freshwater (especially after a dive in saltwater); press the buttons to dislodge any dirty/saltwater left that could hinder the computer's mechanism. Once the computer has been cleaned, store it in a dark and dry place.

Buyer's guide for a dive computer

Choosing your computer

Getting a computer for yourself is an important decision in your diving adventure. As a diver, you need to make sure you have the appropriate dive computer for your needs and for your diving goals.

Recreational/entry-level diving: For recreational diving, any dive computer will work properly. The important informations are going to be your no-decompression limit and your current depth: As a recreational diver, you'll need to ensure you never go below your maximum allowed depth, and that your no-decompression limit stays above zero. Recreational dive computers are usually very varied in terms of choices for personalization: as such, you'll be able to match the color of your computer with your mask, fins, and the rest of your equipment! Good starting computers that are easy to use (and that we recommend) are computers such as the Mares Puck or the Cressi Neon. If you are just starting out, we don't recommend a computer with too many functionalities and instead advise sticking to the basics until you feel comfortable (of course, if you know diving is for you, and want to buy yourself a computer that you know will go further, feel free to buy a more advanced computer right away).

Technical/advanced diving: Technical/Confirmed divers may want more functionalities from their dive computers. An important feature of technical dive computers is the degree of personalization available for the decompression plan and models. As a technical diver, you should keep a certain degree of control regarding the decompression plan: A proper technical diving computer will allow the user to modify certain key parameters, such as used gases, the maximum allowed ppO2, the conservatism/gradient factors, and the depth of the last stop, among others. Some computers may even allow the user to choose the decompression model. If you are getting your first technical diving computer, we recommend getting the Shearwater Peregrine, while if you're already a confirmed technical diver, a computer such as the Shearwater Perdrix 2, or the Garmin Descent MK3 will be more suited to your needs.

Lifestyle/fitness computers: Those kinds of dive computers are wrist-worn dive computers that can double as a fitness watch while the diver is outside of the water; for instance, they can track the heart rate of the user, their sleeping schedule, can be used to set alarms, track the sleeping pattern, etc... There is no debate; if this is the kind of dive computer you are after, we strongly recommend one of the Garmin Descent series (There are a lot of options to choose from in this series, from the more basic Descent G1 to the complete model Descent MK3). In addition to being perfect lifestyle watches, they are also very comprehensive dive computers, featuring many advanced capabilities (such as helium/trimix integration) that many other dive computers lack.

Price Range

Entry-level computer: The most basic dive computers can cost anything between 200€ and 350€. Those dive computers are perfect for beginners as they provide the necessary informations, while not being too expensive! They are great for a first computer.

Mid-range computers: Mid-range computers are priced between 400€ and 800€. They are dive computers with more features, more robust, and appropriate for serious divers. They will give more insights during/after the dive, such as the dive profile. Examples of mid-range dive computers are the Mares Quad or the Shearwater Peregrine.

High-end computers: The high-end computers are also the most expensive ones. Often priced at more than 800€, with the most expensive ones costing upwards of 1000€, they are the computers with the most capabilities and features. Such computers allow in-depth personalization of the decompression parameters, gas integration via transmitters, CCR compatibility, and more. Examples of High-end dive computers are the Shearwater Perdrix 2, or the Garmin Descent Mk3i.

Best price to quality ratio: If you are looking for a dive computer that doesn't break the bank, while still having a decent amount of features, we recommend the Garmin Descent G1 or Garmin Descent G2. While being a mid-range computer in terms of price, its features are those of a high-end dive computer, such as helium blends, personalization of gradient factors, on top of being an all-around lifestyle/fitness computer.

F.A.Q.

Q: What is TTS?

A: TTS (which stands for Time-To-Surface) is the planned time (in minutes) it will take a diver to reach the surface from their current depth. The TTS takes the ascent rate, decompression stops (and possible safety stops) into account.

Q: Is it mandatory to dive with a dive computer?

A: The legality of diving without a dive computer will vary between countries, and the policy can vary between dive centers as well. Regardless of its legal status, we strongly recommend always diving with a dive computer, especially on deeper dives, to ensure you don't accidentally go beyond your maximum allowed depth and your no-decompression limit.