In this article, I want to go over the process of planning a decompression dive, from setting the goal of the dive to having an actionable plan.

Decompression dives are a type of technical dive: this means that direct ascent to the surface is not possible, and the diver will use more technical and specified equipment, which requires additional training. On technical dives, the diver should be self-reliant: this doesn't mean that they should dive alone, but rather, they should plan for failure and have backup equipment for every piece of essential equipment they use. On decompression dives, the "ceiling" is not a physical one like you would find in a cave or a wreck, but rather a so-called "soft-ceiling" resulting from the obligation of the diver to off-gas inert gas before surfacing: if the diver ignores this "soft-ceiling", they put themselves at high risk. The gist of planning a decompression dive is that the diver should know exactly how much decompression they are planning on doing and plan accordingly. Of course, it is a little more complex than that, so let's see in detail how exactly a decompression dive is planned!

Setting the Target

Before getting into the water and before even drafting up a plan, it is important to set the target, or the goal of the dive. You will need to understand:

- What will happen during the dive, and what is the dive about? - Define if it is a training dive, an exploration dive, a fun dive, or something else?

- Who will be part of the dive? - Knowing this allows you to establish a dive plan, knowing everyone's experience level, comfort, and limitations. Even on technical dives, the dive plan should be adequate for the least experienced diver in that group.

- Where the dive will take place - This is very important as it will allow you to prepare the dive plan according to the environmental conditions: a decompression plan for a dive in a dark, cold Swiss lake is very different from one for warm Mediterranean waters. Knowing things like current and visibility, and temperature in advance can help you adjust the conservatism of the dive plan, while other conditions, such as altitude, directly affect the decompression plan.

The most common decompression model used today (Bühlmann ZHL-16C) uses Gradient Factors to control the conservatism of a dive. Every technical/decompression diver should understand how gradient factors work if they use them. If you don't understand gradient factors yet, read this article, which explains them in more detail and how to use them.

On a more abstract note, visualizing the goal and understanding the context of the planned dive will improve your mental readiness.

Generating the decompression plan

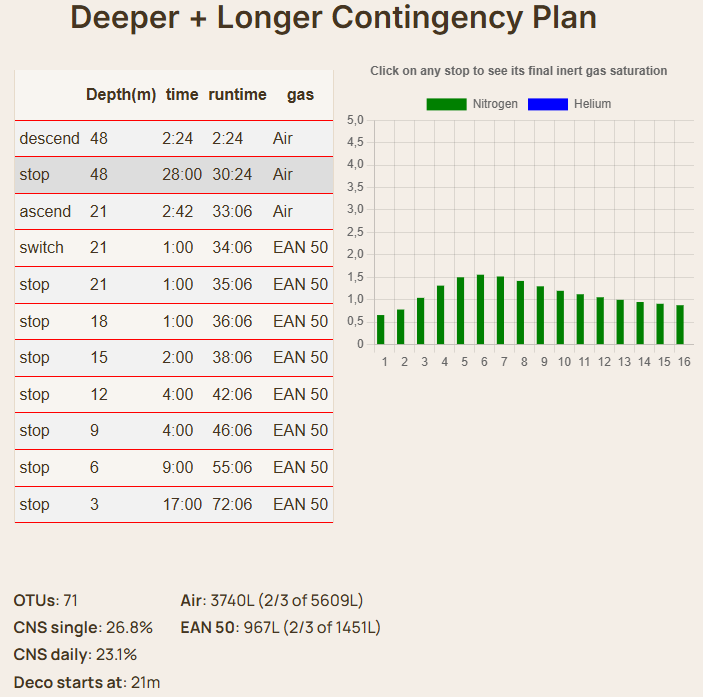

To generate a decompression plan, you will need access to decompression planning software, such as our own online decompression planner, or MultiDeco, for example. Those software programs, using current decompression models such as Bühlmann ZHL-16C/B or VPM/VPM-B, will take the user input (which consists of the target depth, duration, gas used, and decompression gas available) and generate a decompression plan. Modern decompression softwares allow the user to choose their own parameters, such as Gradient Factors/Conservatism, altitude, water density, and more.

A decompression plan is a key tool, as it will allow us to calculate key limiting factors, such as the gas volume required, the total decompression time, the TTS (Time-To-Surface), and more.

To use the decompression software and generate your plan, you will first need to define:

- What is the maximum depth/target depth

- How much time will be spent there

- What bottom gas will be used at these depth

- What decompression gas will be available

Once you entered that information in the decompression planner, make sure you set the parameters accordingly:

- Select the appropriate decompression model and conservatism.

- Make sure the set water density and altitude are entered accurately.

- Additional parameters such as ascent/descent rate and SAC rate should also be entered.

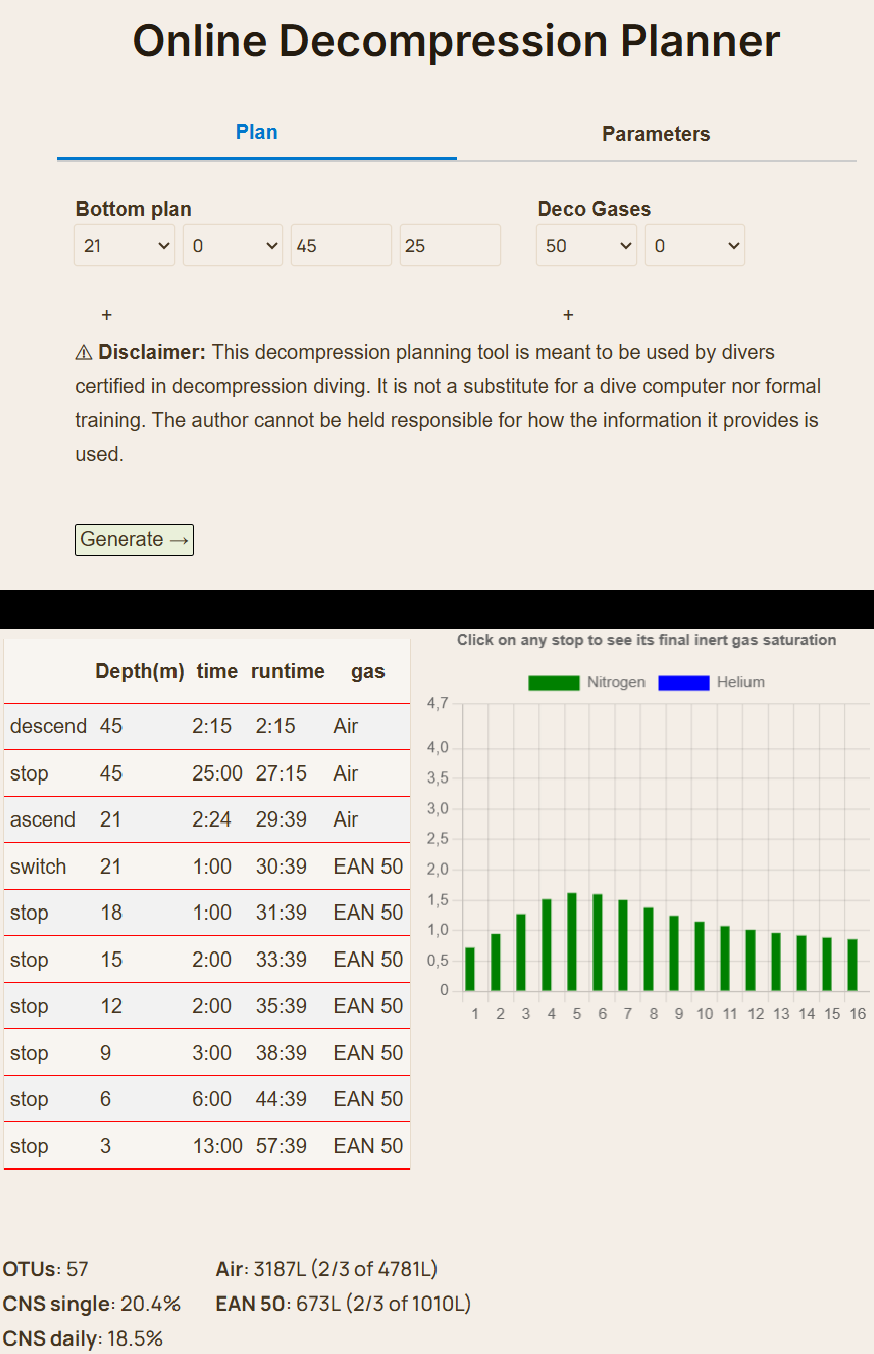

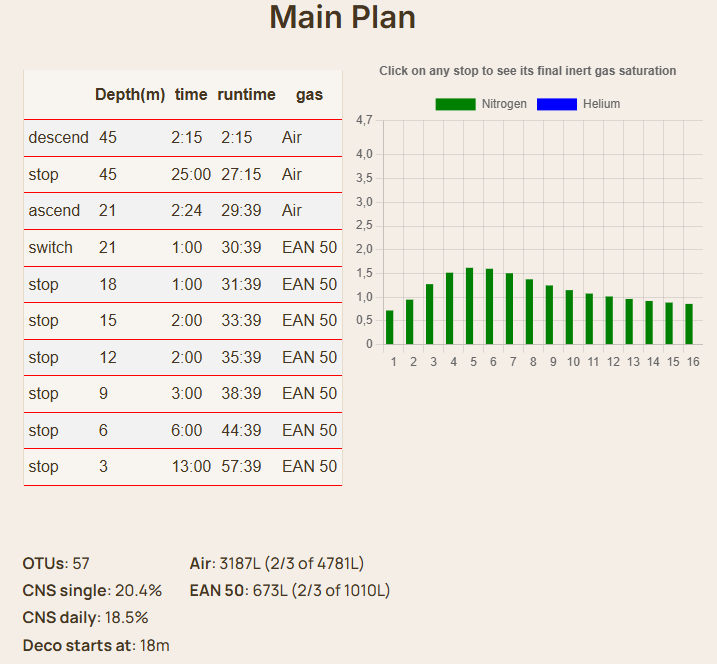

Once the bottom plan is entered and the parameters are set, you can run the software, and it will give you a decompression plan to follow. To give you an idea, using a decompression software to generate a decompression plan of a dive, including a bottom time of 25 minutes at 45 meters using Air, with a decompression gas of 50% Oxygen available, would yield the following plan (Using the ZHL-16C model with gradient factors of 40/85).

As you can see, this specific decompression software also includes a report about the gas requirements and the oxygen toxicity limits (Nevertheless, we will still talk about how to calculate them manually later on in this article).

Now that we have generated a decompression plan, we must have a look at key limiting factors and either validate this plan or reject it. On top of looking at the limiting factors in the main plan, we will want to plan for failure: this means planning for a deeper & longer contingency plan (i.e. if something unexpected happens during the dive), and planning for a lost gas scenario (if our decompression gas becomes unusable for whatever reason) - if you are using multiple decompression gases, you will have to generate a lost gas plan for each of the decompression gases. If any limiting factors on any plan are exceeded, the initial plan will have to be revised (such as reducing the bottom time). The limiting factors we will look at are:

- Total Decompression time

- Total available gas

- OTU limit (pulmonary O2 toxicity)

- CNS limit, single & daily (CNS O2 toxicity)

Once we are sure all the limiting factors aren't exceeded, we'll be able to use the validated plan to find the turn conditions (more on that later).

Validating limiting factors

To illustrate each of the points, we will use the following plan (generated previously) as an example:

Total Decompression Time

Although some divers might not think of the total decompression time as a limiting factor, some entry-level technical courses will only allow a certain amount of decompression. For example, the SSI XR - "Extended Range" course limits the diver to 25 minutes of decompression. This is the easiest of the limiting factors to figure out: just add up the total time of the mandated stops.

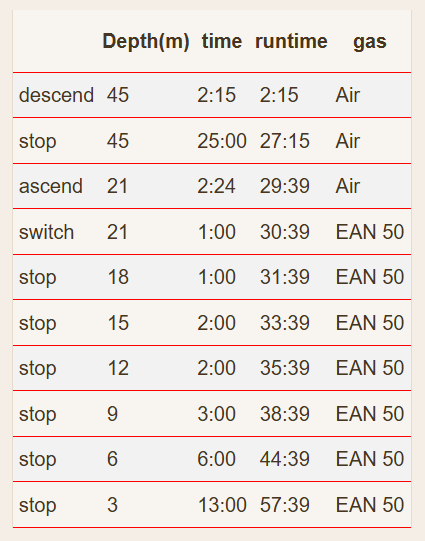

Using the example above, we have a 1-minute stop at 18 meters, a 2-minute stop at 15 meters, a 2-minute stop at 12 meters, a 3-minute stop at 9 meters, a 6-minute stop at 6 meters, and a 13-minute stop at 3 meters. This totals to 27 minutes of decompression. In this case, if the diver actually were limited to 25 minutes of decompression, they would have to either reduce the depth or the time of the bottom plan. To give you an example, reducing the depth to 43 meters and the bottom time to 23 minutes would yield this table:

Counting the decompression time again, we now find it to be only 21 minutes.

Total available Gas

To understand how much gas can be used on the dive, we first need to know how much available gas we have. To find out the quantity of gas available, we can simply multiply the volume of the cylinder by the pressure of the cylinder containing the gas: Quantity = Volume × Pressure.

For example, a common configuration for a decompression dive would be using a twinset (2×12L) as a backmount and an ALU80 (11.1L) as a decompression stage. Say the backmount is pressurized to 220bar, and the stage is pressurized to 200bar. We can then calculate the quantity of gas available for each:

Back gas = 2 × 12 L × 220 bar = 5280 bar L

Deco gas = 11.1 L × 200 bar = 2220 bar L

Now, of course, on the dive, we want to be conservative and avoid getting too close to an empty tank: this is why we add a safety margin. The rule of thirds is a commonly used system to calculate this safety margin. In Cave diving, the rule of thirds states that you should use at most 1/3rd of your gas for the entry phase of the dive, another 1/3rd to return, and the last 1/3rd shouldn't be used, and left as a "buffer". For a decompression dive, we use the rule of thirds to ensure that 1/3rd of the total gas remains after running the whole decompression plan. What this means, if we use our example again, is that out of the back gas and deco gas, we can only use the following amount during our dive:

Back gas: 2/3rd of 5280 bar L = 3520 bar L

Deco gas: 2/3rd of 2220 bar L = 1480 bar L

Now that we know exactly the maximum allowed amount of gas, we can use the generated dive plan to calculate our total gas consumption. To do that, we need to know our SAC rate (if you don't know what a SAC rate is, read the linked article, as it is an important part of planning a dive). As a quick reminder, the SAC rate, or "Surface Air Consumption rate", is the breathing rate of the diver, in Liters per minute. To use it to calculate the quantity of used gas, we can calculate, for each depth:

Quantity = SAC × Pressure at Depth × Time

During a descent or an ascent, we can use the pressure at the average depth: for example, during an ascent from 45m to 21m, we can use the pressure at (45+21)/2 = 33m or 4.3 bar.

It is common for decompression divers to consider two different SAC rates: one for the bottom part of the dive, and one for the decompression part of the dive. Historically, the bottom SAC rate has been considered to be higher than the deco SAC rate due to the higher taskloading at depth. We will need to take each step of the decompression plan individually and calculate the used gas for each one, adding everything up (for each gas) at the end.

Using 20L/min of bottom Sac rate, 15L/min of decompression sac rate, and using the previous plan as an example, we can calculate:

- Descend: (0+5.5)/2 bar × 20L/min × 2.25 min = 124 bar L (air)

- Stop: 5.5 bar × 20L/min × 25 min = 2750 bar L (air)

- Ascend (5.5+3.1)/2 bar × 20L/min × 2.4 min = 207 bar L (air)

- Switch 3.1 bar × 20L/min × 1 min = 32 bar L (air)

- Stop 2.8 bar × 15L/min × 1 min = 42 bar L (EAN 50)

- Stop 2.5 bar × 15L/min × 2 min = 75 bar L (EAN 50)

- Stop 2.2 bar × 15L/min × 2 min = 66 bar L (EAN 50)

- Stop 1.9 bar × 15L/min × 3 min = 86 bar L (EAN 50)

- Stop 1.6 bar × 15L/min × 6 min = 144 bar L (EAN 50)

- Stop 1.3 bar × 15L/min × 13 min = 254 bar L (EAN 50)

Which brings the total air to 3113 bar L, and EAN 50 to 658 bar L.

Comparing those values to our limit of 3520 bar L for air, and 1480 bar L for EAN50, we can see that gas is not a limiting factor for this dive. If we exceeded the gas limit, we would also have to reduce the bottom time, or depth to reduce the total consumed gas.

OTUs

OTUs, also called "Oxygen Toxicity Units," allow divers to track prolonged exposure to high oxygen partial pressure, to prevent onset of pulmonary oxygen toxicity (different from CNS oxygen toxicity, which is the next part). To track OTUs, we can use the following OTU table:

| ppO2 (bar) | OTUs/Min |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.00 |

| 0.6 | 0.27 |

| 0.7 | 0.47 |

| 0.8 | 0.65 |

| 0.9 | 0.83 |

| 1.0 | 1.00 |

| 1.1 | 1.16 |

| 1.2 | 1.32 |

| 1.3 | 1.48 |

| 1.4 | 1.63 |

| 1.5 | 1.78 |

| 1.6 | 1.92 |

| 1.7 | 2.07 |

| 1.8 | 2.21 |

it shows how many OTUs accumulate per minute as a function of ppO2. To calculate the Total OTUs accumulated during the dive, we will need to compute each step individually and sum the results (once again, for ascents/descents, use the average depth). Once we calculated the total accumulated OTUs, we can use the following REPEX OTU Limit chart, to ensure we haven't exceeded the maximum tolerated amount:

| Days | OTU Daily Average | OTU Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 850 | 850 |

| 2 | 700 | 1400 |

| 3 | 620 | 1860 |

| 4 | 525 | 2100 |

| 5 | 460 | 2300 |

| 6 | 420 | 2520 |

| 7 | 380 | 2660 |

| 8 | 350 | 2800 |

| 9 | 330 | 2970 |

| 10 | 310 | 3100 |

| 10+ | 300 | 300×Ndays |

Once again, let's take the previous decompression plan as an example (You will notice, we round up the ppO2 used to choose the OTU/min, to be more conservative):

- Descent (0+5.5)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.58 bar ppO2 --> 0.27 OTU/min × 2.25 min = 0.61 OTU

- Stop 5.5 bar × 0.21 = 1.16 bar ppO2 --> 1.32 OTU/min × 25 min = 33 OTU

- Ascent (5.5+3.1)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.90 bar ppO2 --> 0.83 OTU/Min × 2.4 min = 1.99 OTU

- Switch 3.1 bar × 0.21 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 0.47 OTU/Min × 1 min = 0.47 OTU

- Stop 2.8 bar × 0.5 = 1.4 bar ppO2 -->1.63 OTU/Min × 1 min = 1.63 OTU

- Stop 2.5 bar × 0.5 = 1.25 bar ppO2 -->1.48 OTU/Min × 2 min = 2.96 OTU

- Stop 2.2 bar × 0.5 = 1.1 bar ppO2 -->1.16 OTU/Min × 2 min = 2.32 OTU

- Stop 1.9 bar × 0.5 = 0.95 bar ppO2 --> 1 OTU/Min × 3 min = 3 OTU

- Stop 1.6 bar × 0.5 = 0.8 bar ppO2 --> 0.65 OTU/Min × 6 min = 3.9 OTU

- Stop 1.3 bar × 0.5 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 0.47 OTU/Min × 13 min = 6.11 OTU

Total: 55.99 OTU

The OTU limit varies as a function of the repetitive exposure days of consecutive diving. Nevertheless, even for multiple days, this amount of Oxygen Toxicity Units doesn't come close to the daily limit, and therefore can be validated for the plan.

To actually reach the OTU limit, the diver would need to significantly extend their bottom/decompression time with a high ppO2 and do multiple dives per day for multiple consecutive days.

CNS

CNS, similarly to OTUs, allows us to track our oxygen exposure, but instead of pulmonary O2 toxicity we are trying to mitigate, here, we are trying to mitigate the onset of "Central Nervous System" Oxygen toxicity. CNS Oxygen toxicity is not calculated with a unit, but rather as a percentage (i.e. what percentage of your maximum tolerance did you reach). There is both the single-exposure CNS to track (how much CNS% you got on a single dive), and the daily CNS (how much did your CNS% increase over 24 hours). To calculate both, we can use the following tables:

| ppO2(bar) | CNS single-dive limit (min) | CNS daily limit (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.6 | 45 | 150 |

| 1.5 | 120 | 180 |

| 1.4 | 150 | 180 |

| 1.3 | 180 | 210 |

| 1.2 | 210 | 240 |

| 1.1 | 240 | 270 |

| 1.0 | 300 | 300 |

| 0.9 | 360 | 360 |

| 0.8 | 450 | 450 |

| 0.7 | 570 | 570 |

| 0.6 | 720 | 720 |

The way we are going to calculate our single-dive and daily CNS exposure is the same way we calculated the OTUs: take each step of the decompression plan individually, calculate its ppO2 exposure, and cross-reference to the table above how long we are allowed to be exposed to this specific ppO2, then calculate what percentage of this limit we reach on this specific step; at the end add all the values together. We will have to do this for the single-dive and daily limit separately. For a specific step, to calculate its percentage,we can simply use:

CNS% = (Time spent/Time allowed) × 100

Let's go over our example plan and figure out the single-dive and daily CNS% we would potentially get from this deco dive:

Single-dive:

- Descent (0+5.5)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.58 bar ppO2 --> 2.25min/720 min × 100 = 0.3%

- Stop 5.5 bar × 0.21 = 1.16 bar ppO2 --> 25min/210min × 100 = 11.9%

- Ascent (5.5+3.1)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.90 bar ppO2 --> 2.4min/360min × 100 = 0.7%

- Switch 3.1 bar × 0.21 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 1min/570min × 100 = 0.2%

- Stop 2.8 bar × 0.5 = 1.4 bar ppO2 --> 1min/150min × 100 = 0.7%

- Stop 2.5 bar × 0.5 = 1.25 bar ppO2 --> 2min/180min × 100 = 1.1%

- Stop 2.2 bar × 0.5 = 1.1 bar ppO2 --> 2min/240min × 100 = 0.8%

- Stop 1.9 bar × 0.5 = 0.95 bar ppO2 --> 3min/300min × 100 = 1%

- Stop 1.6 bar × 0.5 = 0.8 bar ppO2 --> 6min/450min × 100 = 1.3%

- Stop 1.3 bar × 0.5 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 13min/570min × 100 = 2.3%

Total: 20.3%

Daily:

- Descent (0+5.5)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.58 bar ppO2 --> 2.25min/720 min × 100 = 0.3%

- Stop 5.5 bar × 0.21 = 1.16 bar ppO2 --> 25min/240min × 100 = 10.4%

- Ascent (5.5+3.1)/2 bar × 0.21 = 0.90 bar ppO2 --> 2.4min/360min × 100 = 0.7%

- Switch 3.1 bar × 0.21 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 1min/570min × 100 = 0.2%

- Stop 2.8 bar × 0.5 = 1.4 bar ppO2 --> 1min/180min × 100 = 0.6%

- Stop 2.5 bar × 0.5 = 1.25 bar ppO2 --> 2min/210min × 100 = 1.0%

- Stop 2.2 bar × 0.5 = 1.1 bar ppO2 --> 2min/270min × 100 = 0.7%

- Stop 1.9 bar × 0.5 = 0.95 bar ppO2 --> 3min/300min × 100 = 1.0%

- Stop 1.6 bar × 0.5 = 0.8 bar ppO2 --> 6min/450min × 100 = 1.3%

- Stop 1.3 bar × 0.5 = 0.65 bar ppO2 --> 13min/570min × 100 = 2.3%

Total: 18.5%

In both cases, the CNS% value is far from the limit, which means that the CNS is not a limiting factor for this dive either (the limit should be considered to be lower than 100%: in general, it isn't recommended to exceed 80% CNS).

Now that all the limiting factors have been verified, the main plan can be validated, which means that it would be a safe plan to conduct. Of course, as decompression/technical divers, we want to plan for any mishap that could happen, and therefore, we'll need backup plans as well.

Generating the Backup plans

There are usually two types of contingency plans technical divers prepare:

- A "Deeper & longer" plan, where the diver accidentally stayed longer at the bottom, and/or went deeper, which will lead to a longer decompression schedule.

- A "lost gas" plan, where one of their decompression gas gets lost/becomes unusable. In this case, the diver must ensure they have enough backgas gas to complete their decompression with one less decompression gas. If the diver uses multiple decompression gases, they will have to generate a "lost gas" plan for each of those gases.

The idea behind generating contingency plans is that by looking at the key limiting factors on those plans, we can predict, if something goes wrong, our capcity to safely complete the dive.

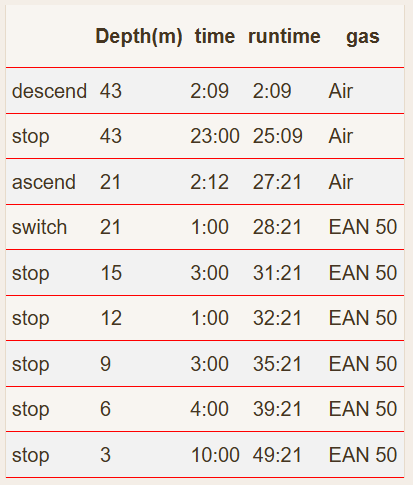

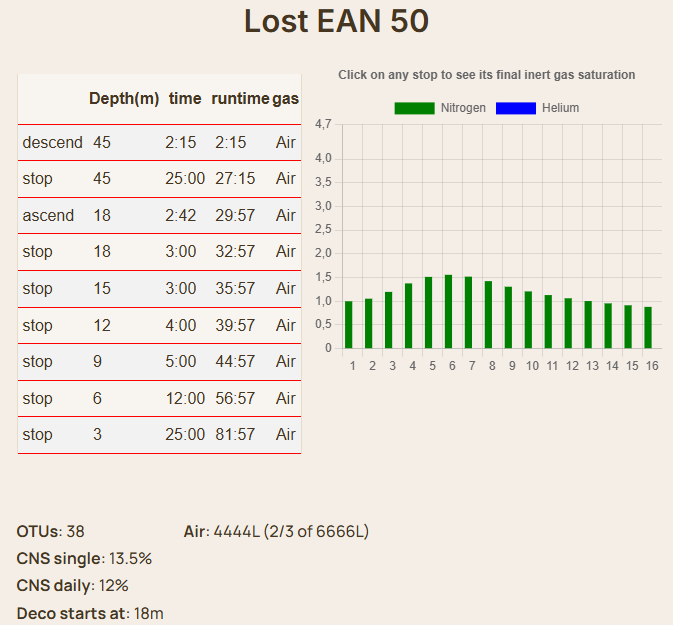

To generate such plans, you can tweak the initial parameters: for the deeper+longer contingency plan, increase the bottom time and depth; for the lost decompression gas plan, remove the decompression gas from the plan. although modern decompression tools, such as our own free decompression tool will automatically generate those extra plans:

On top of this, if the decompression tool gives you an automatic report of the limiting factors, it prevents you from having to re-calculate 3 them over and over again. If it doesn't give you a report, you will have to repeat the previous steps for all plans. You must then validate that all contingencies are realistic (enough gas to complete each plan, CNS and OTU not exceeded).

There have been discussions about respecting the rule of thirds in the contingency plans, as planning for contingency on contingency can quickly make a dive unrealistic. The answer to what you should do in that scenario completely depends on your personal conservatism. If you want to plan everything properly, make sure you have enough gas to complete the contingency plan and still have a large portion of gas left over. For this reason, the SAC rate used to calculate the used gas is usually inflated.

If any key limiting factors in the contingency plans are exceeded, the initial plan will need to be rethought. On the other side, if all contingency plans are validated, the main plan is, in turn, validated as well.

Turn conditions

Now that we have validated the main plan, we can use it to figure out our turn conditions. Turn conditions are the variables which will signal the bottom part of the dive is over, and the diver will need to initiate their ascent to start their decompression. Knowing and following turn conditions will prevent the diver from exceeding their plan. The following turn conditions will need to be monitored with the assistance of a dive computer. On a decompression dive, the diver should always have a minimum of two dive computers in case on fails.

Run time

The first turn condition to follow is the run time. The decompression plan, alongside the depths and the time for each stop, will also generate a "runtime" column, which is the consecutive sum of all time spend at all previous stops. Once the runtime of the bottom part of the dive is over

For example, using our previous plan, we can see that the runtime at the end of the bottom part is 27 min 15s. This means that once the total dive time reaches 27 min 15s, it will be time to start the ascent.

TTS

TTS, or "Time To Surface", is a way to measure how much time will be required to reach the surface from the moment we start the ascent (including ascent time and decompression stops). To calculate the TTS using a decompression plan, simply subtract the bottom runtime from the total runtime. To monitor the TTS during the dive, you will need a dive computer that calculates it in real time. Some dive computers have advanced features, such as the "TTS + 5 mins", which would allow the diver to know in advance what their TTS will be in 5 minutes.

Taking the example of our dive plan, we can calculate our TTS to be 57:39 - 27:15 = 30 min 24s.

Turn Pressure

The turn pressure is the minimum amount of pressure left required in the backgas. To calculate the turn pressure, we must calculate what the maximum quantity of consumed gas is during the bottom part of the dive, and translate that into pressure in the cylinders.

For example, imagine the cylinders we are using for the air is a twinset (total of 24L) filled to 220 bars. As calculated previously, we know that gives us a total quantity of 5280 bar L. We can then calculate how much gas we expect to use during the bottom portion of the dive (before the ascent):

- Descend: (0+5.5)/2 bar × 20L/min × 2.25 min = 124 bar L (air)

- Stop: 5.5 bar × 20L/min × 25 min = 2750 bar L (air

Total: 2 874 bar L

To convert that to a pressure in the cylinder, we simply have to divide by the volume of the cylinder: 2874 bar L / 24L = 120 bar. This means that we expect to use a maximum of 120 bar in our backgas.

Given that we start at 220 bar, after using 120 bar, we would be left with 220bar -120 bar = 100 bar. This is our turn pressure: it means that the rest of the plan (including the contingency plan) is based on the assumption that we will have at least 100 bar of pressure left in our backgas.

Conclusion

Now we have 3 decompression plans (1 main, 1 contingency, and 1 lost gas) which will need to be copied on some kind of wetnotes to be accessible during the decompression dive, and we know what our turn condition are:

- A Runtime of 27 min 15.

- A TTS of 30 min 24s.

- And a turn pressure of 100 bar.

If any of those conditions are met during the dive, the diver will have to initiate the ascent and follow the decompression plan. Alternatively, the decompression plan can be used as a support, and the diver will follow their dive computer's instructions.

It is important to understand that following this article alone is not enough to make a decompression dive "safe", as the diver will need to master basic skills such as perfect buoyancy, or safe gas switching procedures. Those skills can only be learnt in a controlled environment on a course, not online.