Few subjects in the realm of scuba diving are as confusing to divers as Nitrogen Narcosis: although most seasoned divers have had their fair share of experience with narcosis and understand it isn't something that needs to be feared, it isn't uncommon for new and upcoming divers to worry about experiencing it before a deeper dive. Some divers argue they are immune to it, while others say they experience it every dive. With all of these claims, let's discuss what is true and what isn't.

The goal of this article is to explain what Nitrogen Narcosis is, how to deal with it, if you should apprehend it or not, and talk a bit more about the scientific aspect of it: the mechanisms behind it, and the more generalized Inert Gas Narcosis.

What is nitrogen Narcosis?

Nitrogen Narcosis is a temporary affliction that affects divers at depth as a result of the increased nitrogen partial pressure (ppN2). The effects can be compared to a state of drunkenness, or perhaps more accurately, an Anesthetic-induced numbness. Although the depth at which Narcosis becomes noticeable varies from person to person, the main effects start past 30 meters of depth (~100 feet) and alleviate upon shallowing. The effects of nitrogen narcosis are often informally described by what divers call Martini's law:

Signs and Symptoms of Narcosis

The effects of Nitrogen Narcosis vary with depth: the deeper you go, the more intense the effects of narcosis will be. Conversely, to reduce the impact of Narcosis, simply shallowing up until the effects diminish is enough. Although mild symptoms might be hard to perceive as narcosis, they will become obvious past a certain point. Breathing regular air, the first noticeable symptoms of nitrogen narcosis usually appear past 30m, and include:

- Mild Euphoria

- Impaired Reasoning and reduced Motor coordination

- Mild dizziness

- Overconfidence

Past 50m (164 feet), more symptoms appear, and/or existing ones significantly worsen, including:

- Euphoria developing into anxiety

- Confusion

- Blurred vision/hallucinations

- Panic/terror

- Sleepiness

Beyond 90m (295 feet), the symptoms aggravate and may include:

- Intense dizziness

- Visual and Auditory alterations

- Loss of consciousness

There hasn't been evidence that people can acclimatize (on the same dive) nor adapt (between multiple dives) to narcosis. However, experienced divers are more likely to make informed decisions, even when under the influence.

Multiple factors can affect the onset and the intensity of Nitrogen Narcosis: it can vary from person to person, but can also be affected by things such as recent alcohol consumption, tiredness, exertion, rate of descent, temperature, and age, among other things. Narcosis isn't necessarily consistent: this means that for the same dive done twice, the narcotic effects may feel more intense in one than the other.

Historically

The first recorded instance of nitrogen narcosis is believed to be in 1835, when Junod, a French scientist, reported that while breathing compressed air, "The functions of the brain are activated, imagination is lively, thoughts have a peculiar charm, and, in some persons, symptoms of intoxication are present." This was described again by Paul Bert in 1878 in his publication "La Pression barometrique".

At the beginning of the 19th century, after the first industrial revolution, when the use of caissons was becoming common (for mining, excavation, building bridges, etc...), scattered reports of workers feeling inebriated or acting strangely while under pressure were appearing in various publications and journals. Although the cause was still a mystery, it was clear that something was affecting workers who exposed themselves to increased pressure.

After John-Scott Haldane published the first dive tables in 1908, allowing divers to plan staged decompression stops, the range of accessible depth increased significantly. This led the U.S. Navy to conduct multiple test dives to test those limits: One of those dives was during the salvage of the USS F-4, a submarine that sank during training off the coast of Hawaii. Divers went up to a depth of 90 meters (295 feet) to fix lifting chains under the hull of the sunken submarine. Although the salvage operation was successful, the divers who went to those depths reported feeling intense dizziness and were subjected to severe narcosis. This limitation for deeper dives led the Navy to try to add some helium in the mix, which seemed to have a positive effect on the narcosis: this successful test run led to the establishment of the United States Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) in 1927, which published the first heliox tables in 1939.

Narcosis during recreational dives

Although it isn't a topic of concern for new divers (as open-water divers are limited to 18 meters, where narcosis isn't an issue), when they complete a certification that allows them to dive deeper (usually to 30 or 40 meters), the instructors should have a workshop, followed by an in-water session to assess how narcosis affects the mental capacity/decision process of the diver. This is usually done by completing some sorts of psychometric tests at the surface, and then at depth, comparing the time it takes to complete them in both environments. This gives the diver an idea of how they are affected by Narcosis, even if they don't necessarily realize it.

As the first effects of narcosis become apparent beyond a depth of 30m, the maximum recreational depth of 40 meters is well within the range where narcosis can be encountered. This being said, the effects at these depths will be rather mild and won't pose any risk.

The truth is that although recreational divers may experience symptoms of narcosis, it won't be a big issue, if not a point of discomfort for some. Nevertheless, even recreational dives should be planned (maximum depth, maximum bottom time or no-deco limit time to respect, return pressure, etc...), and the main issue that may arise in "narked" divers is that their overconfidence can surpass their judgement and lead them to ignore the dive plan: exceeding their maximum allowed depth, exceeding the no-decompression limit, or staying at depth with insufficient pressure in their tanks, which can lead to dangerous situations.

Narcosis on deeper dives

As explained previously, the deeper one goes, the more intense the effects of Nitrogen Narcosis will become. For recreational depths, it isn't much of an issue, but for technical divers, who wish to venture deeper, narcosis can quickly become a limiting factor. As the depth parameter is not changeable in this scenario, technical divers will have to instead modify the gas mix they use to reduce the narcotic effects, as simply diving on air won't be an option.

Deep diving on air is a controversial topic: in the recreational realm, either using air or nitrox is very standard. Some divers/agencies claim that no one should dive past 30m on air due to its narcotic potential; despite that, it isn't uncommon to see divers regularly go past this depth, to 40 meters or even beyond. Using air past 57 meters, narcosis will become relatively intense and won't be the only issue to take into account as the partial pressure of oxygen will surpass 1.4 atm (which puts the diver at risk of Oxygen Toxicity). Due to that, it is very uncommon (and heavily unrecommended) to dive with air past ~55m. The divers who ignore these warnings have to deal with a significantly higher risk of oxygen toxicity and intense narcosis, which will heavily cloud their judgment.

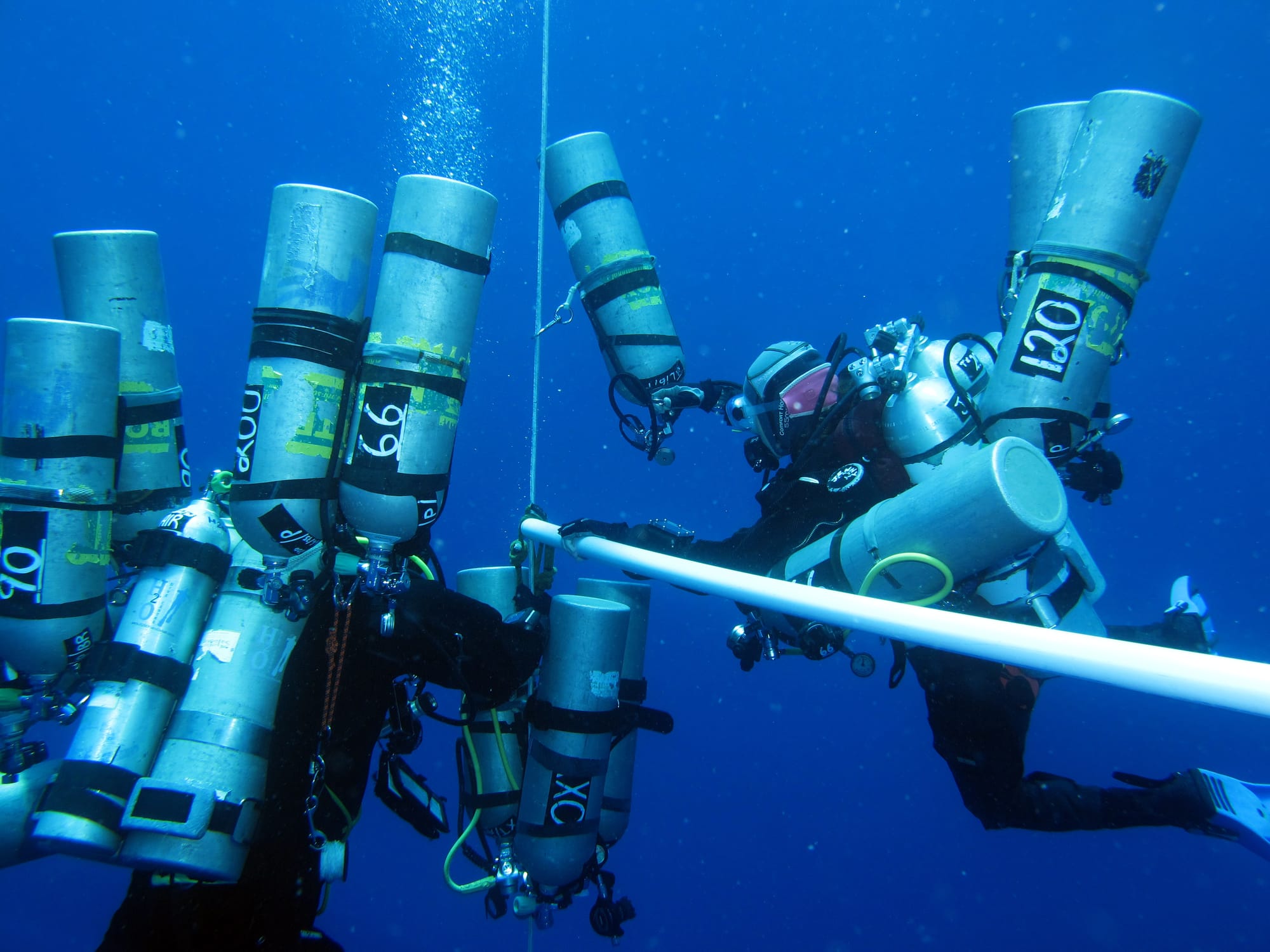

To prevent all of those issues from arising, technical divers add helium in their breathing mix: this reduces the narcotic potential of the mix (as helium has a very weak narcotic potential) and allows the diver to go deeper safely. Air/nitrox with added helium is commonly called trimix, and divers need to have a specific formation to use trimix. If you are interested in diving with trimix and want to learn more, you can read this article.

Handling Nitrogen Narcosis

First of all, you should understand that -as already stated- narcosis isn't dangerous if the dive plan is respected. Nevertheless, the possibility of being affected by it might make some divers uncomfortable, so here is the guide on how to handle nitrogen narcosis:

The first step is knowing how to reduce its effects: whilst impossible to get rid of completely, there are some ways to minimize them. Being well-rested, limiting alcohol intake, and generally maintaining a healthy lifestyle are all recognized ways to have a positive impact on the onset of narcosis. Before the dive, it is also important to have a clear mind: prepare a thorough dive plan, and ensure everyone is ready to follow it. Depending on the conditions of the dive site, you can already know if you can expect to feel some effects: cold and murky water will enhance the narcotic effects compared to warm, clear water; if you are susceptible to being cold, wearing an appropriate suit and being comfortable will help reduce the symptoms of narcosis.

Once in the water, descending as slowly as possible to the maximum depth will also reduce the effects of narcosis. At the maximum depth, if any signs or symptoms appear, it is up to the diver: most divers don't mind (some actually quite enjoy the feeling), but if you start feeling uncomfortable, let your buddy/buddies know, and start shallowing up gradually, until the effects disappear. While you can find it to be intimidating, what will really help you is getting more experience: the more dives you do and the more of a comfortable diver you become, the less narcosis will be an issue, even if the effects never disappear!

Inert gas narcosis

Although we have called it Nitrogen Narcosis thus far for the sake of simplicity, it would be more accurate to call it Inert Gas Narcosis because nitrogen isn't the only gas with narcotic effects: Every inert gas can have a narcotic effect at depth (even Oxygen, which isn't actually inert, as it is metabolized by our body). The only reason we talk about nitrogen more than the other gases is that it is more common to find nitrogen in our breathing mix, given that it is found in air at a proportion of 78%, and compressed air is the easiest mixture to get a hold of for recreational diving. Nevertheless, let's have a look at how various gases behave, going from least narcotic to most narcotic:

- Helium: Helium is the least narcotic gas, and therefore the most common substitute for deep dives to reduce the narcotic potential of a gas mix. Besides air, it is also one of the most researched gases for breathing. A blend containing only Helium and Oxygen is called Heliox, while a blend containing Helium, Oxygen, and Nitrogen is commonly called Trimix. Although Helium theoretically has a small narcotic potential, there has been evidence showing that it might actually not be narcotic at all. Some drawbacks of Helium include its high thermal conductivity, which makes it a bad insulator on colder dives, its high cost (deep trimix dives can cost hundreds of €), and its potential to cause HPNS in divers beyond 150m of depth.

- Neon: Neon has a narcotic potential of about 1/3 that of Nitrogen. Although it is very rarely used as a breathing gas, there have been experiments up to a depth of 366 meters (1200 feet) without signs of narcosis. On top of that, it is lighter than nitrogen and a better thermal insulator than helium. Its main drawback compared to helium is its higher price: Helium is already quite expensive, which can be a limiting factor for many divers, but Neon is even more expensive.

- Hydrogen: Hydrogen is also a possible substitute to reduce the narcotic potential of a blend, as it has a relative narcotic potential of 0.6. Hydrogen is cheap due to its abundance: it can be produced from fossil fuels or hydrolysis. The main drawback of hydrogen is its high reactivity, as it can only be used in specific ratios with oxygen. Additionally, while it is less narcotic than Nitrogen, it is still quite narcotic. Hydrogen is used primarily for ultra-deep diving to offset the effects of HPNS.

- Nitrogen: Nitrogen is used as a reference for the narcotic potential of other gases. Its narcotic potential is 1.

- Oxygen: The debate over whether Oxygen should be considered a narcotic or not has been a long-standing one. Some theories (such as the Meyer-Overton Hypothesis, which links the lipid solubility of gases to their general Anesthetic action) would push for it being a narcotic, with a narcotic potential even higher than that of nitrogen. However, there are other mechanisms, such as oxygen being metabolized, and the uncertainty over whether it can bind to neuroreceptors or not, that do not allow us to assert whether oxygen is narcotic or not. Nevertheless, many technical divers consider oxygen to be narcotic: Based on the Meyer-Overton Hypothesis, its narcotic potential is estimated to be 1.6-1.7.

- Argon: Argon has a narcotic potential of 2.3. It is rarely used as a breathing gas due to its higher narcotic potential, but it has been researched as a potential mix for astronauts. The mix of oxygen and argon is commonly known as Argox (and Argonox if it also contains nitrogen!) and is rather used as a gas for drysuit inflation due to its thermal properties.

- Krypton: Krypton has a narcotic potential of 7. Due to its high density, high price, and high narcotic potential, it is not used as a breathing gas.

- Xenon: Xenon has a narcotic potential of 25.6 (25 times higher than Nitrogen!). Due to its extremely high narcotic potential, it isn't used as a breathing gas; However, it is used as an anesthetic in medical settings!

Mechanism

Due to the complexity of the physiology of the human body in hyperbaric conditions, it is difficult to precisely describe the mechanism behind inert gas narcosis and pinpoint its cause (particularly because there are multiple factors that come into play). Nevertheless, the research on it is quite vast, and there are many theories we can look into.

- The Junod Hypothesis is wrong but still interesting to talk about: it was the first attempt at describing the mechanisms behind nitrogen narcosis, and theorized that it was the increase in pressure itself that would enhance the blood flow and excite the nerve centers. The Moxon Hypothesis theorized that the increase in pressure would force the blood into areas of the body where the normal oxygenation process cannot take place, which would cause this narcosis. Both theories were proven wrong due to the fact that using a different blend (trimix, for example) would reduce the narcosis, while keeping the pressure constant.

- The Meyer-Overton Hypothesis, describing inert gases, conjectures that the narcotic potential of the gases correlates with their lipid solubility: the higher the lipid solubility of a gas, the easier it would be for it to penetrate a cell membrane and disrupt the signals between the nerve transmitters. Although various gases don't respect this hypothesis, the Noble gases (listed above) do.

- The Carbon Dioxide Hypothesis theorizes that narcosis would correlate with the carbon dioxide retention in divers: divers breathe gas at an increased density, and the CO2 elimination is not as optimal. However, studies measuring Oxygen and CO2 levels in arterial blood while breathing different mixtures showed that CO2 retention and narcosis are not directly connected and should it be considered as an aggravating factor rather than the primary cause.

- Various physical properties of molecules have been correlated with their narcotic effect, such as the partial molar free energy, the Van der Waals interactions, although there are exceptions for each, which prevent it from being validated.

- Anesthetics under hyperbaric conditions have been shown to expand lipid monolayers and bilayers (i.e. cell membrane). This action is antagonistic to the effect of helium (which isn't narcotic at high pressure), which contracts the lipid layers, and is believed to lead to HPNS. This is why ultra-deep divers use a combination of helium and a gas (often hydrogen) with anesthetic properties.