As divers venture deeper and deeper, there are more risks and factors to take into account: Inert gas narcosis, Oxygen toxicity, Decompression obligations, etc... Most of those issues have simple solutions; for instance, reduce the amount of Oxygen in your mix to reduce the onset of oxygen toxicity, however, past a certain depth, the issues divers encounter become more challenging and harder to deal with. Amongst deep divers, HPNS is recognized as one of those issues, and is also known as one of the last barriers to overcome.

HPNS, also known as High-Pressure Nervous Syndrome (or High-Pressure Neurological Syndrome), is a syndrome characterized by multiple signs and symptoms that manifest when a diver breathes a helium-based mixture at depth greater than 150 meters (~500 feet). Some of the symptoms include decreased mental cognition and motor functions, tremors, nausea, and dizziness.

Discovery of HPNS

HPNS is believed to have been first described by Russian Scientist G. L. Zal'tsman in 1961. While experimenting on animals and humans with a heliox mix and simulating dives between 131-152 meters, he observed tremors, which he coined helium tremors, although he did note that the tremors seemed to improve the longer the subject stayed at depth. Sadly, his research was only made available to the Western world 7 years later, in 1968.

On their side, Western scientists were also researching the possibility of using helium for ultra-deep diving. As the 20th century was synonymous with the development of more precise decompression models, divers were naturally able to descend deeper. Going deeper on air meant running into the issue of nitrogen narcosis; such a case happened in 1915, when the USS F-4 (An F-Class submarine from the United States) sank off the coast of Honolulu Harbor in Hawaii, at a depth of 92 meters. Although the salvage of the wreck was successful, divers who went to the maximum depth experienced severe vertigo (which we now know to be nitrogen narcosis). This -and other instances- kicked off the research on using a helium-based mix, as it was recognized to be beneficial for reducing narcosis on deep dives.

By substituting the nitrogen with helium (heliox mixes), researchers did not expect to encounter additional narcotic effects induced by the helium, or other complications due to Carbon dioxide, until the 300-400m mark. However, in 1965, during an experiment where divers were gradually compressed to 244m, and had to complete arithmetic exercises, both at 183m and 244m. It was observed that the divers were presenting reduced intellectual performances along with nausea and tremors. The term "High-Pressure Nervous Syndrome" was coined by Peter B. Bennett, one of the leading scientists in the realm of diving and high-pressure environments (he is also the founder of DAN).

By the late 60s/early 70s, research about HPNS was well on its way, and various research organizations were researching its effects, origins, and how to minimize it.

What is HPNS?

As mentioned before, HPNS is an affliction that occurs to divers who dive super-deep (It is usually said the threshold is 150m, but the depth can actually vary, as we'll see later) while breathing a helium-based breathing mix. Mainly characterized by tremors in the appendages, accompanied by reduced motor and mental performances, the effects of HPNS increase in proportion to the total depth and the speed of compression. Although they can be as trivial as tremors and slight nausea at shallower depths (we have to use the word "shallow" carefully here, as we are still talking about important depths), if the diver goes deeper or goes down at a faster rate, more symptoms appear. The symptoms of HPNS include:

- Tremors, including postural tremors (Specifically in the limbs and the torso)

- Myoclonic spasms (muscle twitching)

- Decreased motor and mental performances

- Nausea, dizziness, and drowsiness

- Change in brain wave activity

During the experiments, scientists had different ways to measure and quantify the extent of the effect of HPNS, such as using an electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure brainwaves, assessing motor and cognitive abilities using psychomotor tests, and measuring tremors with transducers.

It was recognized that the effects of HPNS were distinct from the potential narcotic effects of helium, as there were clear differences between the two:

- At constant depth, the effect of narcosis didn't show improvement over time, while symptoms of HPNS seemed to improve.

- Divers suffering from narcosis did not present tremors

- In divers suffering from HPNS, alpha-band activity decreased, and theta-band activity increased proportionally with depth. In divers affected by narcosis, activity in the alpha-band increased while theta waves remained unaffected.

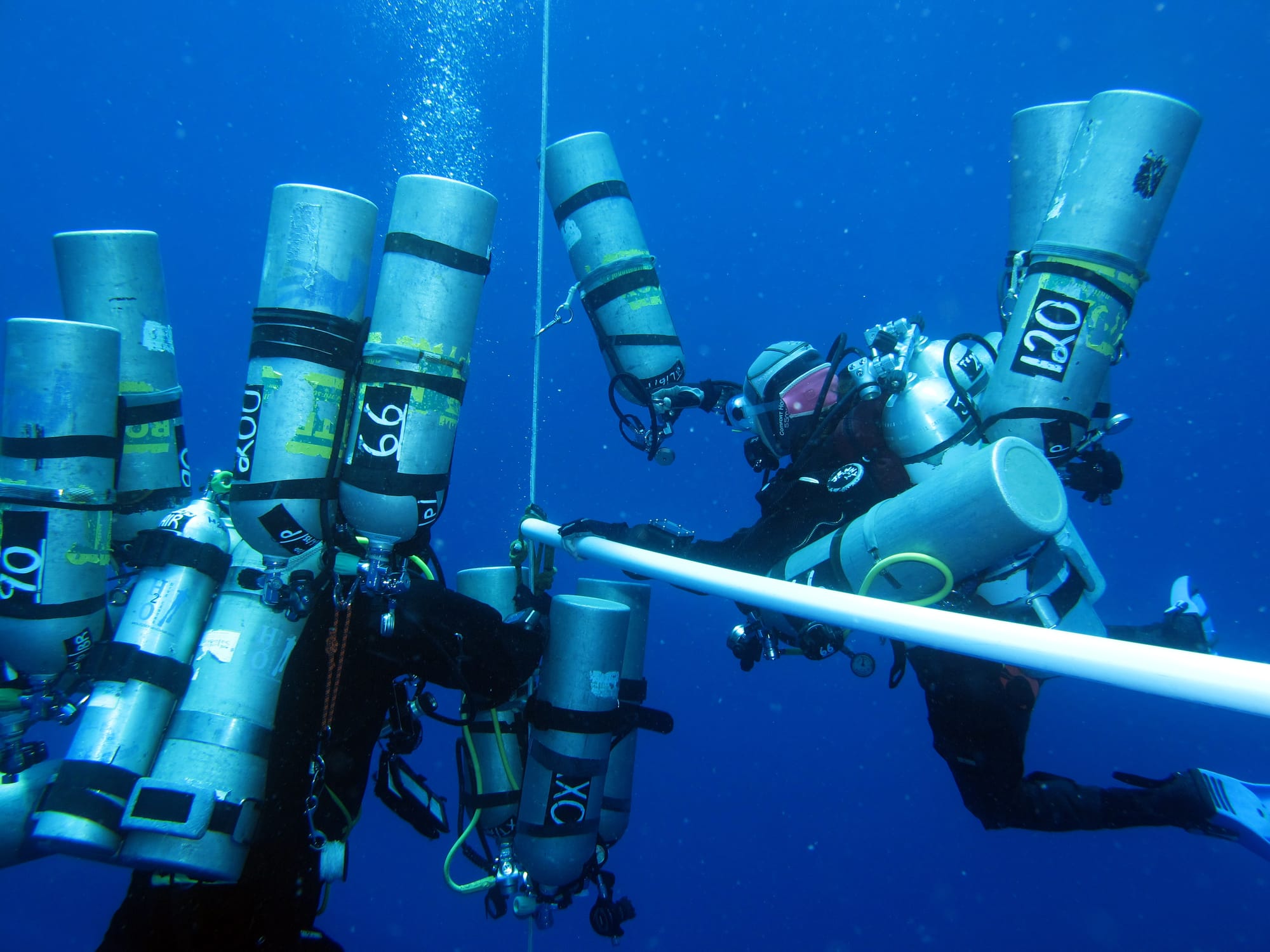

In extreme cases, pursuing the dive or continuously increasing depth could lead to convulsions. This was observed on a dive with squirrel monkeys, who were compressed down to 625m: tremors started appearing between 183-251m, followed by EEG spikes between 457-503m, after which, at the maximum depth of 625m, the squirrel monkeys started convulsing. As EEG changes in humans were appearing shallower (~300m) than those observed in the squirrel monkeys, it was theorized that the convulsion could also occur shallower in humans. Using this data, a maximum theoretical depth of around 360m was given for how deep humans could go. Of course, as human curiosity is limitless, researchers didn't wait long to test this theoretical limit, only to realize that we could, in fact, go deeper by using special precautions to limit the effects of HPNS. In November 1992, all of this culminated in the deepest simulated dive to date, led by COMEX, a French company known for deep-sea research and being one of the leaders in researching how to use hydrogen as a breathing gas: Théo Mavrostomos reached a simulated depth of -701m over 43 days by us Hydreliox (a combination of hydrogen, helium, and oxygen).

Preventing HPNS

Although completely avoiding HPNS proves to be rather difficult, researchers discovered multiple ways to attenuate or delay the effects.

The first parameter that was discovered would impact the onset of HPNS, and unfortunately, could not be controlled, was individual susceptibility; it was discovered that everyone had a different "tolerance" to it. While some divers could go to 400m and still complete tasks successfully, others would encounter partial loss of consciousness and other incapacitating symptoms from 250m on. It was shown that divers could be classified into one of three categories by compressing them to 180m and monitoring how the theta-band activity in the frontal region of their scalp evolved:

- The first group showed less than a 10% increase in their theta waves.

- The second group showed an increase between 10-100%

- The third group showed an increase of more than 100%

It is inadvisable for a diver belonging to the third group to go as deep as divers belonging to the first two groups.

The second parameter that was observed to have an impact on the intensity of the symptoms and the depth at which the HPNS would appear was the speed of compression: it was first theorized by COMEX that slowing down the rate of compression could alleviate HPNS symptoms. This theory was su*/ccessfully tested many times, significantly decreasing the rate to a few meters per hour, and sometimes including longer stops at intermediate depth to allow the diver to "adjust" to the pressurized environment. At the depth this was tasted to, it means that the total time to compression sometimes took multiple days. For commercial and industrial applications, this was a problem.

By using an approximate compression speed of 1m/min and by allowing acclimatization stops at intermediate depths, multiple dives to 300m were completed with minimal hindrance from HPNS symptoms. Nevertheless, even by minimizing the compression parameter as much as possible, HPNS could not be ignored beyond depths of 400m.

The third parameter researchers used to limit the effects of HPNS was by introducing narcotic or anesthetic gases into the mix breathed by the diver. This was first noticed by G. L. Zal'tsman in 1961, who identified that the narcotic effect of nitrogen was countering the tremors induced by the helium. By using trimix and comparing its effect to heliox at similar depths, a significant reduction in tremors, dizziness, and nausea was observed. Of course, by reducing the symptoms of HPNS and reintroducing narcotic gases at those depths meant that the divers might be subjected to narcosis. Nitrogen wasn't the only gas observed to have a positive impact on HPNS symptoms; other gases with positive effects included Hydrogen and Nitrous Oxide. Although the exact mechanism by which the gases interact and counteract each other isn't exactly understood, by studying the interaction of each gas with a lipid monolayer, it was observed that helium (and neon) would increase its surface tension, while Nitrogen, Hydrogen, Nitrous Oxide (and even Argon and Oxygen) would reduce its surface tension. This could be a potential explanation for the antagonism of HPNS between the gases. It was found that for faster compressions up to 300m, a ratio of 1:10 N2:He could be used effectively to offset the effects of helium.

Mechanisms of HPNS

Before attempting to explain where HPNS comes from, it is important to understand that the exact cause(s) are complex to pinpoint due to all the factors that come into play. Nevertheless, there are some prevalent theories about the origin of HPNS:

- The high helium pressure directly affects the CNS, although the exact part of the Central Nervous System which causes HPNS is not confirmed, it is theorized that the tremors and myoclonus originate from the peripheral nervous system, spinal cord, or brain stem.

- As explained previously, another potential explanation is that the helium, at high pressure, increases the tension of lipid layers on the cell membrane, which could in turn affect receptors, proteins found on the membrane, and more.

- The role of certain neurotransmitters has been studied in relation to HPNS symptoms. Some neurotransmitters that stand out are GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate), dopamine, and serotonin. Higher activity in NMDA receptors is believed to cause hyperexcitability in the CNS under hyperbaric conditions. Conversely, the inhibition of GABA neurotransmission seems to promote HPNS symptoms.

- The high-pressure helium environment might inhibit the propagation of signals between synapses.

Note: This whole article is based on the work published by Peter B. Bennett and David H. Elliott, Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving, 5th Edition (2003) pp. 323 - 357 (The High Nervous Pressure Syndrome)