Gradient Factors are a very important part of technical diving and planning decompression dives. Despite that, it is still a very grey area for a lot of divers, sometimes even confusing dive instructors. In this article, I will dive deeper into diving theory to demystify gradient factors, explain exactly what they represent, how they affect a dive, and how to choose them according to your preferences.

M-values and gradient

To understand gradient factors, we'll first need to understand what m-values are (you can read the linked article to get a more in-depth understanding of it).

To recap, the general idea is that modern decompression models describe the human body as being "compartmentalized". Each of those compartments saturates (on-gas) and desaturates (off-gas) at a specific speed characterized by their respective half-times. Faster tissues on-gas and off-gas faster, while slower tissues on-gas and off-gas slower. Once these compartments (notice how I use the term tissues and compartments interchangeably) are saturated in nitrogen, the m-value of these compartments describes how much nitrogen each compartment can tolerate before presenting signs of DCS. This m-value varies as a function of ambient pressure (depth) and also varies from compartment to compartment.

When getting into decompression diving, our tissues will supersaturate to an extent where surfacing directly poses a significant risk of DCS. The goal for the diver will then be to decompress gradually as they come up: off-gassing enough nitrogen at specific depths, while staying under a safe level of saturation during the ascent. Although the m-value of each compartment decreases during the diver's ascent, it is still important that the diver is shallow enough (shallow can be relative, as the first decompression stops will depend on the depth and the duration of the bottom time, during which the diver is on-gassing) to desaturate him/herself.

Gradient Factors help us in that regard; they provide a quantitative way of staying below the m-value while still being able to off-gas. But let's not jump ahead of ourselves just yet. Before getting into gradient factors, let's understand what gradients are: Gradients represent the difference in pressure between the dissolved nitrogen in our body and the total ambient pressure, it uses the m-value of each compartment as a reference; a gradient of 1 means the compartment is at its m-value, while a gradient of 0 means the compartment is at ambient pressure (it can and is also often expressed as a percentage). If we know the m-value of a compartment at a certain ambient pressure (if you want to learn how to calculate them, you can read this article), and how much nitrogen is dissolved in the compartment at that point in time, we can calculate the gradient using the following formula:

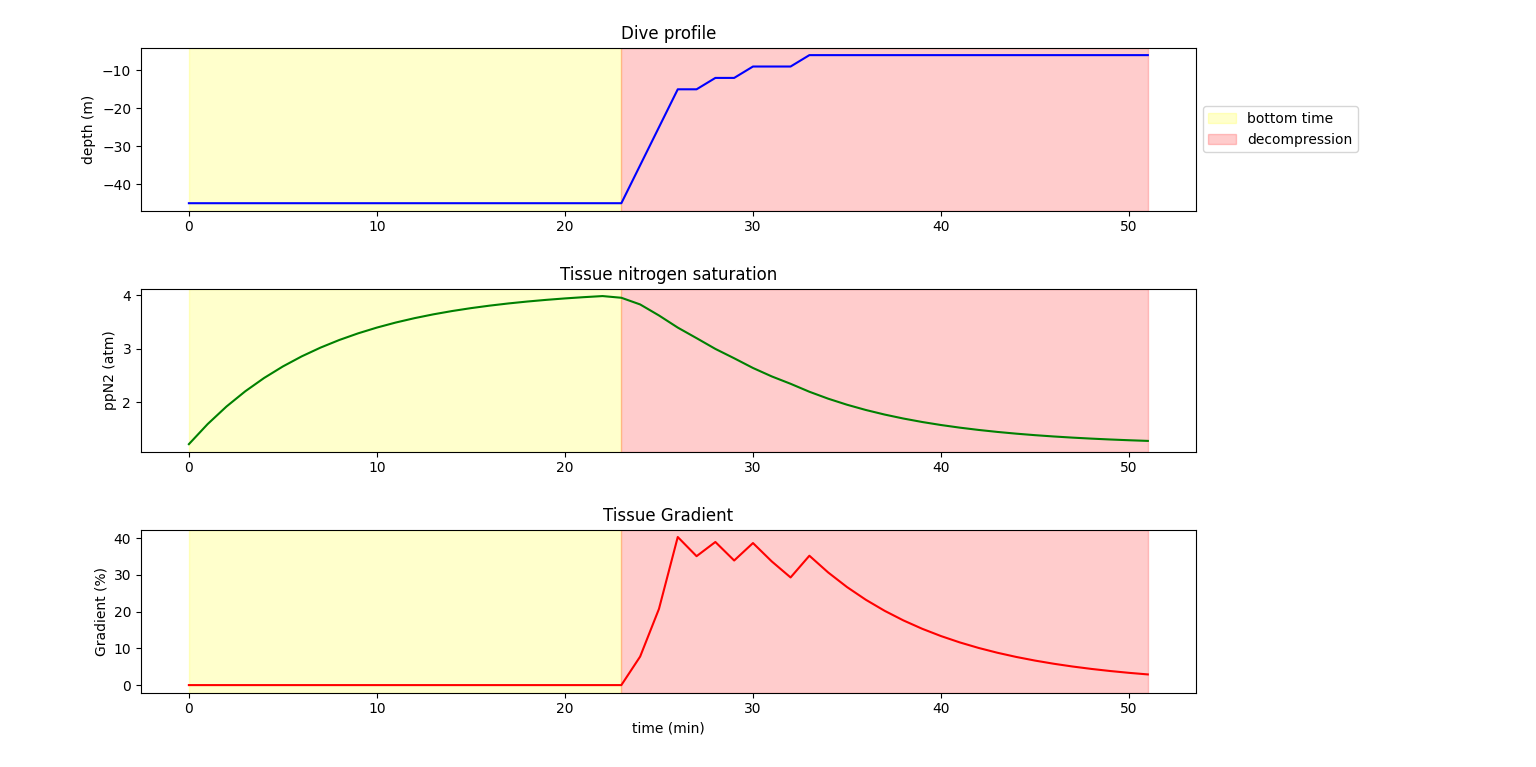

\[ \text{Gradient} = \frac{P_{compartment} - P_{amb}^{inert}}{mvalue - P_{amb}^{inert}} \]An important concept to keep in mind is that the gradient of each tissue changes with depth: for a given nitrogen load, the gradient increases as depth decreases. You can imagine the gradient as being the nitrogen "pushing" itself out of our tissues; the greater the pressure difference, the more the nitrogen is pushing. The graph below shows how the gradient of a compartment changes throughout a dive:

In the example above, we are tracking the nitrogen saturation and gradient of the first compartment throughout a dive. The first part of the dive consists of a bottom time of 23 minutes, after which the diver initiates his ascent and completes certain decompression stops. We can observe that the gradient stays at 0% during the whole bottom time, even though the compartment is on-gassing: this is because the compartment saturation level is lower than the ambient nitrogen pressure. Once the diver starts to ascend, the pressure induced from the nitrogen present in the tissue becomes greater than the ambient nitrogen pressure, and therefore, the gradient increases sharply. The sets of "teeth" we can see on the graph depicting the gradient show how short and increasingly shallower decompression stops affect it: the nitrogen off-gases on the stops, making the gradient drop, but when the diver shallows up to the next deco stop, the gradient re-increases. Once the diver is at the final deco stop (6m), the compartment finishes the off-gassing process, and the gradient drops as well. An interesting observation to make is that the tissue off-gases faster when the gradient is high; once the gradient drops, so does the off-gassing speed.

As a gradient of 100% in a tissue means that the nitrogen load is equal to its M-value, we want to stay as far away from it as possible. The issue arises when we stay too far away: staying too deep to avoid getting closer to a high gradient means that our tissues will be on-gassing. To off-gas properly, our tissues should still have a gradient above 0%.

What are Gradient Factors?

Gradient factors are a way to control the conservatism of a dive: gradient factors consist of two numbers, GF low, and GF high, usually represented as LOW/HIGH (for example 40/80 is a pretty standard gradient factor setting, 40 is the GF low, while 80 is the GF high).

- GF high represents the percentage of the m-value at which your most saturated compartment is allowed to surface. For example, suppose you have a GF high of 80; in that case, the decompression planner/dive computer will start generating decompression stops once at least one of your tissues has a surface gradient beyond 80%, and the decompression will clear only once they are back under this value. If none of your compartments go beyond that limit, no decompression stops are generated. The higher your GF high is, the less conservative the model is (as you will be closer to your M-value upon surfacing): 60-70 is considered quite conservative, 70-85 is considered moderate, and 85-95 can be considered aggressive.

- GF low represents the percentage of the m-value at which the first stop is generated: if you have a lot of nitrogen in your tissues, it is entirely possible to exceed a gradient of 100% in one or multiple compartments before even reaching the surface. To prevent this from happening, the decompression planning software, or your dive computer, will calculate the depth at which your tissues will reach a certain gradient. For example, if you have a GF low of 40, the first stop will be generated once one of your tissues reaches a gradient of 40%. Keep in mind, the gradient varies with depth; therefore, a gradient of 40% at 10m doesn't mean the surface gradient in the same compartment is also 40% (as a matter of fact, if the surface gradient would be higher).

Once the GF high and GF low are set, the decompression plan will act as a ramp, bringing the gradient in the tissues as gradually as possible from the GF low (at the depth of the first stop) to the GF high (at the surface). During the ascent, between the depth of the first stop and the surface, the tissue will assume all gradient values between GF low and GF high: the idea behind it is to bring the compartments to the highest chosen gradient as gradually as possible.

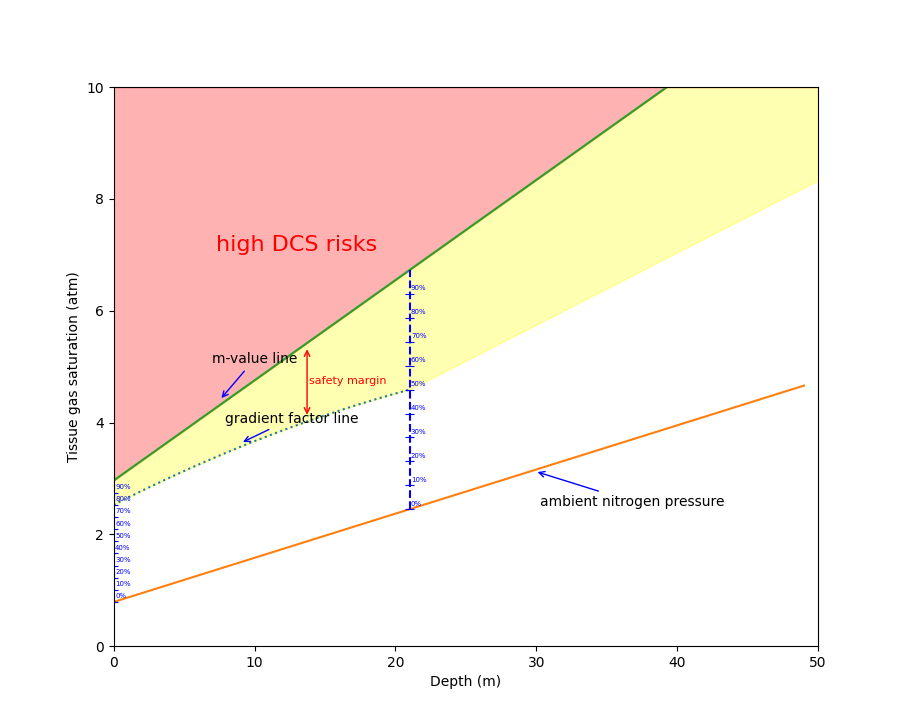

To get a better understanding of how gradient factors work, observe the graph below: the depth is represented on the x-axis, while the tissue gas saturation is represented on the y-axis. Although a diver can find himself anywhere on this graph, the red area (delimited by the m-value line) is to be avoided. Using gradient factors, the diver can stay further away from the m-value line. At any depth, the compartment will saturate or desaturate towards the ambient nitrogen pressure line. When the diver shallows up and moves

Using the same graph, we can actually show how the gradient factor line is used to generate decompression stops: in the following example, the diver chose gradient factors of 50/80.

Keep in mind that the graph above only tracks a single compartment, while most decompression models have to track up to 16 compartments at the same time, ensuring none of them go beyond the gradient factor line and that all of the compartments are below the GF high before clearing the decompression: the way these models deal with that is simply looking at the leading compartment, meaning the compartment that is closest to the maximum allowed gradient factor. Over the course of the dive and the decompression phase, some compartments will overtake others, and the leading compartment will change. This can lead to situations where one compartment is off-gassing while other, slower compartments are still on-gassing.

How gradient factors affect your dive plan

Gradient factors will control your conservatism and will dictate how much decompression you need (or if you need any decompression at all). The higher your conservatism is, the more decompression you will require, and vice versa, the lower your conservatism is, the less decompression you will require. Looking at each parameter individually, the GF High will dictate the "baseline" conservatism: at no point throughout the dive will any of the compartments have a gradient higher than the GF High parameter; this will affect the duration of the decompression phase, as a lower value will mean that the diver will need to off-gas more. The GF Low parameter will control the depth of the first stop:

To give an example, let's have a look at a dive plan using three different levels of conservatism. The parameters of the dive will be:

- The diver will go to a depth of 45 meters for a bottom time of 30 minutes, breathing a 25% oxygen, 75% nitrogen mix.

- The gas used for the decompression phase is a 50% oxygen, 50% nitrogen mix.

- The three different levels of conservatism used will be 45/95 (low conservatism), 40/85 (medium conservatism), and 35/75 (high conservatism).

Here are the results (calculated using MultiDeco as a decompression planning software):

| 45/95 (low) | 40/85 (med) | 35/75 (high) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45 m | 30 min | 30 min | 30 min |

| 21 m | 1 min | 1 min | |

| 18 m | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min |

| 15 m | 1 min | 1 min | 2 min |

| 12 m | 1 min | 2 min | 3 min |

| 9 m | 4 min | 4 min | 4 min |

| 6 m | 19 min | 23 min | 28 min |

| total deco | 26 min | 32 min | 39 min |

We can clearly observe that the higher the conservatism chosen, the more decompression will be needed! Another interesting observation is that for parameters with a lower GF Low, the decompression stops start deeper.

To give a personal anecdote, the parameters I use when I do a decompression dive are 70/70. My reasoning behind it is that since I dive quite often, I like to stay on the safe side, and therefore chose a reasonably low GF High of 70%. The reason why I also have my GF Low at 70% is that I try to avoid deeper decompression stops: when the bottom part of the dive is done, I want to ascend as much as possible to avoid extra on-gassing in my deeper tissues. Using those parameters effectively keeps my maximum tissue gradient at 70% consistently throughout the dive. If we run the same plan as the previous example, but with parameters of 70/70, the decompression plan would be:

| 70/70 | |

|---|---|

| 45 m | 30 min |

| 15 m | 1 min |

| 12 m | 2 min |

| 9 m | 6 min |

| 6 m | 32 min |

| total deco | 41 min |

As we can see, although having such a low GF high extends the total decompression time, having a higher GF low allows us to skip the deeper stops and spend most of the decompression time at the shallower stops.

Choosing gradient factors

In the realm of technical diving, choosing the "best" gradient factor is a very opinionated topic: if you ask 10 different tec divers what the best gradient factors are, you're probably going to get 10 different answers. The truth is that there is no "perfect" choice, and a lot of it comes down to the type of dive you're planning on doing and your own risk tolerance.

If you are not looking at technical/decompression dives and plan on staying in the realm of recreational diving, your deep tissues will not be very saturated in nitrogen, and off-gassing is going to be very fast. In a recreational context, using a higher GF High (85, 90, for example) is not uncommon, although I can still strongly recommend staying on the more conservative side and using a lower GF High of 75 or 80 (even though your bottom time will be limited as your no-decompression limit will be lower). If you are not doing any decompression, the GF Low doesn't matter much.

If you are planning decompression dives and are choosing your gradient factors, the first thing you will look at is the GF High, and set it depending on your risk tolerance and your preferred conservatism. This is up to each and every one, but I would personally consider 65-75 to be conservative, 75-85 to be "normal", and anything above 85 to be quite aggressive. Once your GF High is set, you will choose your GF Low accordingly: if you would like to start decompression deeper (and include so-called deep stops), choose a low gradient factor; if you would like to avoid deeper stops, choose a GF Low with a value close to your GF High. Having a higher GF Low also means you will start your decompression closer to your M-value ceiling depth, and therefore, it is good if the diver is experienced and has proper buoyancy.